For those of us lucky enough to live in peaceful countries, it’s hard to imagine what it means to experience the horrifying events that we see in the news: violence, devastating loss, and living conditions that many of us would consider inhumane. Living through these experiences is extremely challenging. Distress, deep sadness and feeling overwhelmed are all absolutely appropriate responses that shouldn’t be considered signs of illness.

Overusing the words “trauma” and “traumatized” casts refugees as victims, and can have an unintended negative effect. Research shows that while most people experience an appropriate level of distress, only one in five develop mental health problems like depression or post traumatic stress disorder. It also shows that their mental health depends on much more that what they experienced before arriving in host countries; after arrival, the environment that people set out to create new lives in plays a key role for their mental health.

By seeing refugees not as victims, but as people working to redefine who they are after losing livelihoods, loved ones, and their previous social status, we can all contribute to an environment that fosters resilience – the ability to live through extreme difficulties without developing mental health problems.

Acknowledging burden is important. Appreciating resilience is at least equally vital.

Fleeing from war or persecution takes strength and perseverance. When people are referred to as “traumatized” based merely on their status as refugees, the strengths they’re using to cope with extreme adversity and navigate their way to safety tend to go under-appreciated.

It’s not just about war and loss.

Violence and sudden loss before and during the journey to relative safety are rarely the sole cause of distress. “Post-displacement stressors” such as housing insecurity, family separation, changes in social status and family roles, intransparent policies and financial problems are an often under-estimated burden.

Emphasizing trauma can cast refugees as victims, leading to an unintended power imbalance that undervalues people’s sense of control, self-efficacy and esteem.

Without enough opportunities to balance this burden with experiences that reinforce a sense of control and self-efficacy, these stressors can wear on people’s natural ability to cope with the many challenges of achieving safety in a new culture and environment for themselves, and their families.

The right help at the right time

Having arrived in relative safety, both adults and children can continue to experience a lot of distress, for example poor sleep and appetite, jumpiness or irritability, frequent tears or exhaustion. In many cases, these stress symptoms are all appropriate responses to the exertions of flight and resettlement. Under good-enough conditions, we can usually mobilize our natural abilities to stabilize and recover. Without enough opportunities to do so, stress symptoms can develop into mental health problems.

It would seem logical that psychological support is a priority. However, this is only part of the answer. Before the “stress load” of war, flight and resettlement takes a heavy toll on people’s health, there are many things that can lessen it. Reducing the burden of post-migration stressors is essential. Both with regard to good-enough conditions for recovery, and to the efficacy of psychological support.

There are many ways each of us can contribute to an environment that fosters resilience. We all have the capacity for resilience. In order for it to unfold, we need to be able to put it into action. And this is where our environment plays an important role.

How does your environment foster resilience?

Think of the places where you live, work, learn and play. How, when and where do the following happen?

- Access to resources for a healthy and productive life, for example sufficiently safe housing and meaningful occupations.

- Experiences of being in control of our lives, for example opportunities to make choices based on what is important to us.

- Opportunities to be recognized for our skills and competencies, and to use them to contribute to our communities.

- Social connections that reinforce our sense of belonging, self-esteem and value for others.

If you are someone who is engaged in supporting refugee families as they gain foothold in a new and foreign environment, think about how, when and where you can contribute to an environment that fosters these aspects. No matter how small, our actions have an impact on the social ecology that can both promote and hinder resilience.

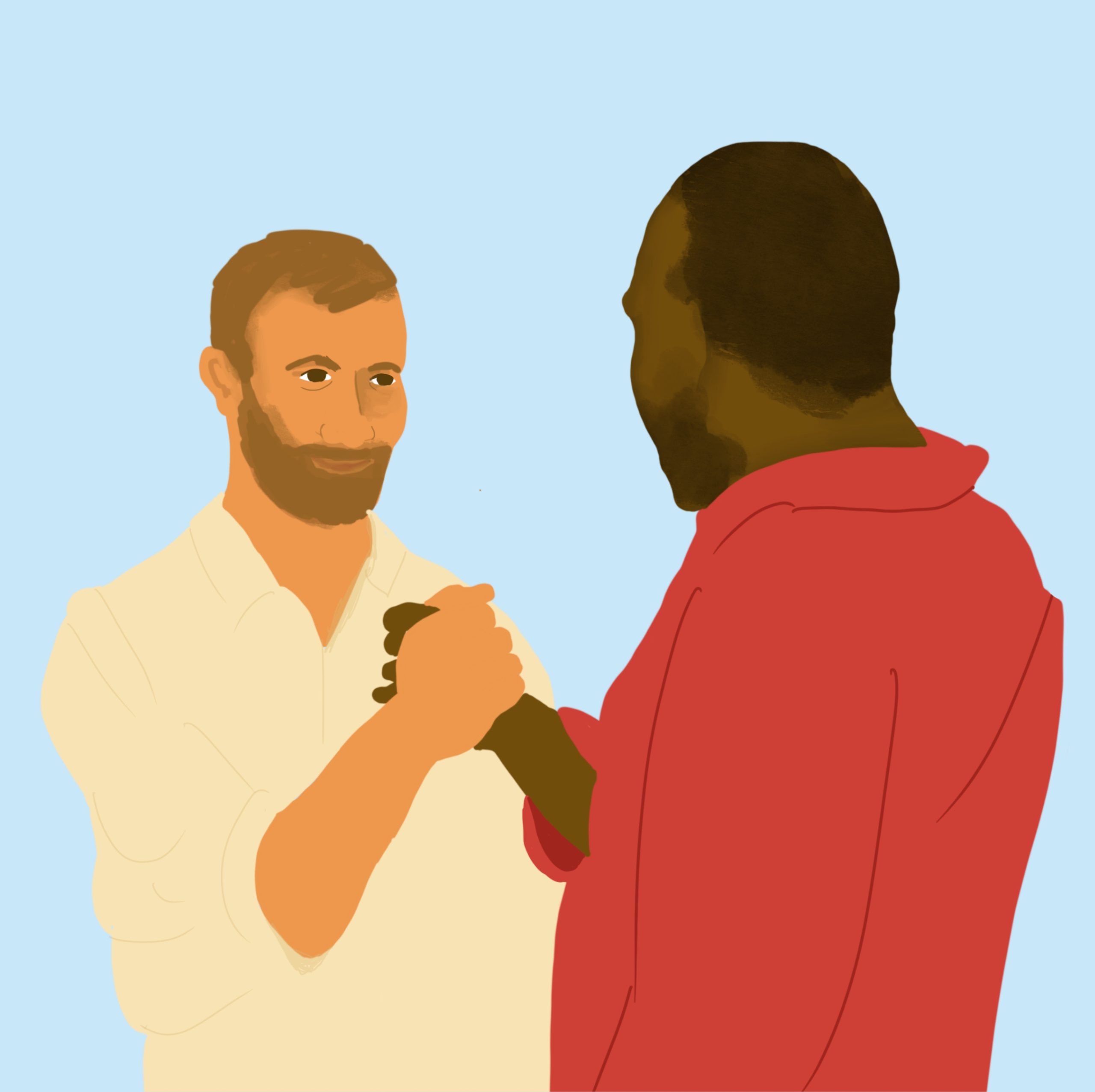

WE’RE IN THIS TOGETHER:

The individual strengths and gifts that each of us has to offer are part of a big picture. Their impact depends on how aware we are for each other’s strengths and gifts, and how well we work together. Appreciating each other’s contributions by asking about and utilising what people bring to the table fosters an environment that promotes autonomy, wellbeing and resilience for everyone involved.

INTENTION SHAPES HOW WE PERCEIVE EACH OTHER

Prioritizing deficits is a natural human response to any kind of stressful situation. When it comes to helping each other through difficult times, we can make a point of widening our perception to include and strengthen what is otherwise often overlooked.

Putting intention into practice

In our interactions as individuals, we can practice including resilience by remembering to ask questions, rather acting on assumptions. For example:

- By bringing your children to safety, you’ve already achieved so much. Now that you are here, what is most important to you when it comes to your family’s wellbeing?

- With everything you’re coping with, finding your bearings and getting settled takes a lot of strength. What is helping you get yourself and your family through this? Even small, everyday things like playing together count!

- What strengths do you have that will help you manage this challenging time?

- What kind of external support would you find helpful?

COOPERATION IS KEY!

As parts of a helper system that aims to support families, we can make a point of contributing to an environment that promotes wellbeing by prioritising cooperation.

Because we tend to focus on deficits under stress, it often goes against our instincts to invest time and energy beyond solutions to immediate problems. But the overall benefit is more than worthwhile if we go about it efficiently.

Again, asking questions is key! Here are some examples:

- How does each partner’s service aim to reduce post-migration stressors in families lives?

- What do each of you do well and how can this support the other’s goals?

What specific problems or needs cannot be met by your service alone?

How can working together help fill this gap, and what changes or improvements will indicate that your cooperation is paying off?

References:

Bogic, M., Njoku, A. & Priebe, S. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 15, 29 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

Marley C, Mauki B. (2019). Resilience and protective factors among refugee children post-migration to high-income countries: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 29(4):706-713. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky232. PMID: 30380016.