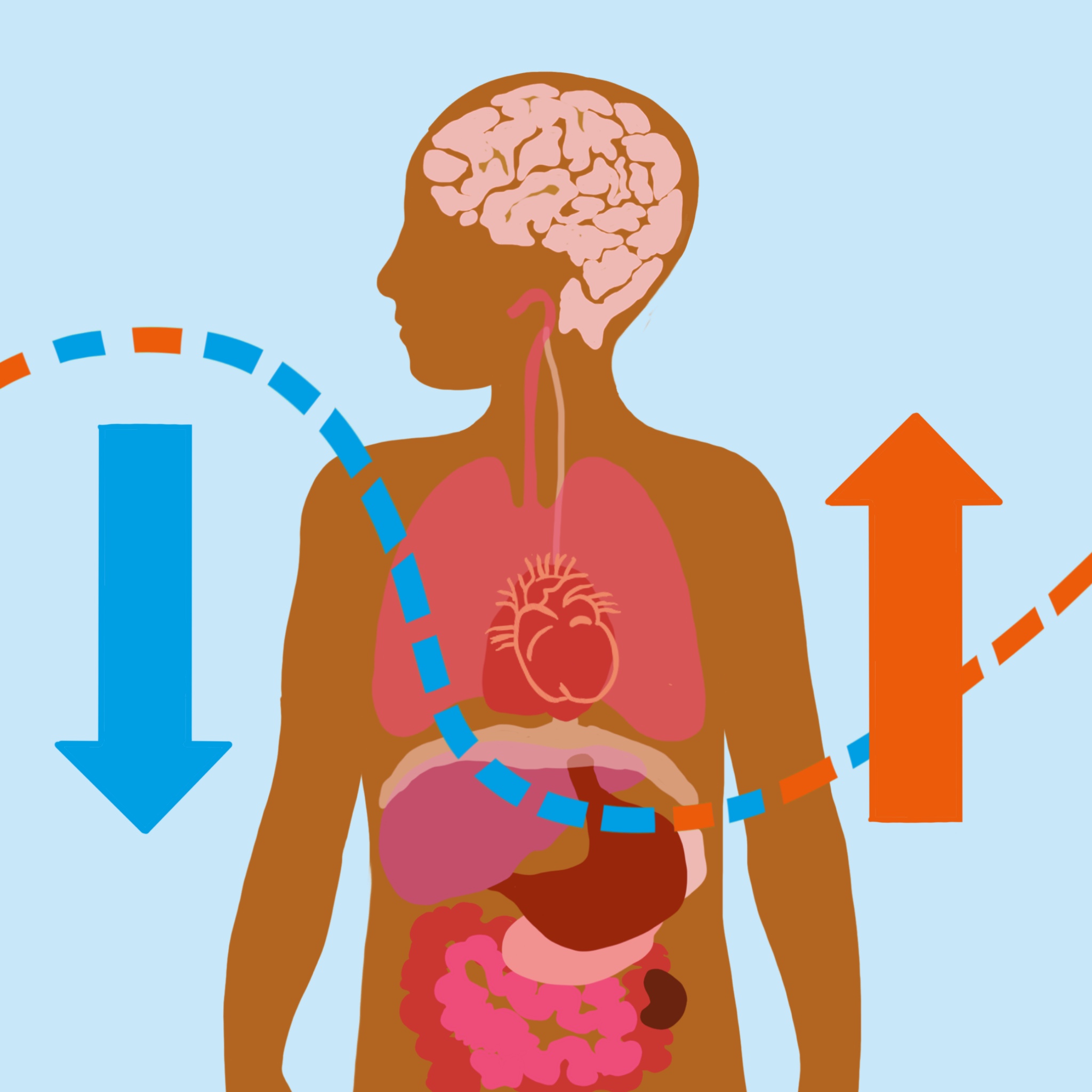

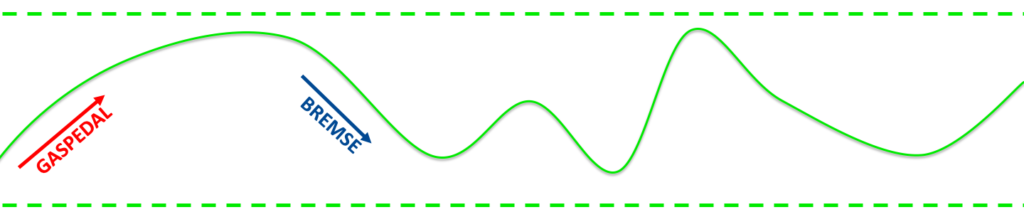

Long or extremely stressful situations affect our bodies, minds and souls. This simple model can help understand why. The “Stress and Recovery Curve” describes how our body keeps an optimal balance between activation and recovery. When activity is called for, the curve goes up. When recovery is possible, the curve goes down. As long as the curve runs smoothly, we are able to adapt to changes around us, to cope with challenges and, most importantly, to respond to people around us in a way that is helpful for both ourselves, and for others.

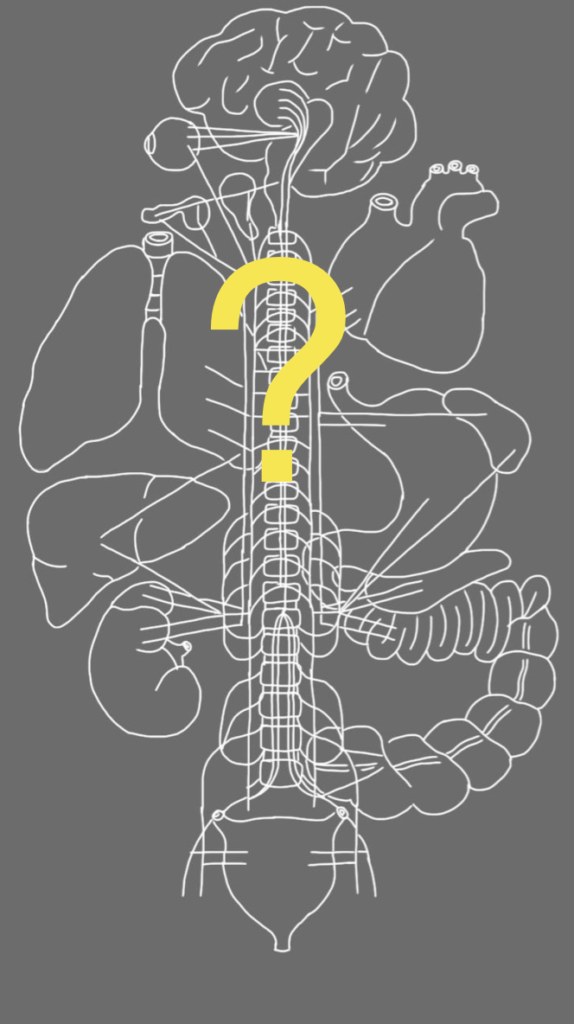

This natural ability to balance stress is biological. Our autonomic nervous system is constantly working to maintain a healthy balance between activation and recovery. It’s called “autonomic” because it usually responds “automatically”. Under normal circumstances, we rarely notice this happening. However, in stressful situations, our nervous systems work much harder than usual.

During this challenging time, it can be helpful to remember:

When our Stress Curve is overtaxed and becomes less flexible, it is a biological response to an abnormal situation.

Because no two people are alike, each of us has an individual Stress- and Recovery Curve that can become wider or narrower, depending on our circumstances.

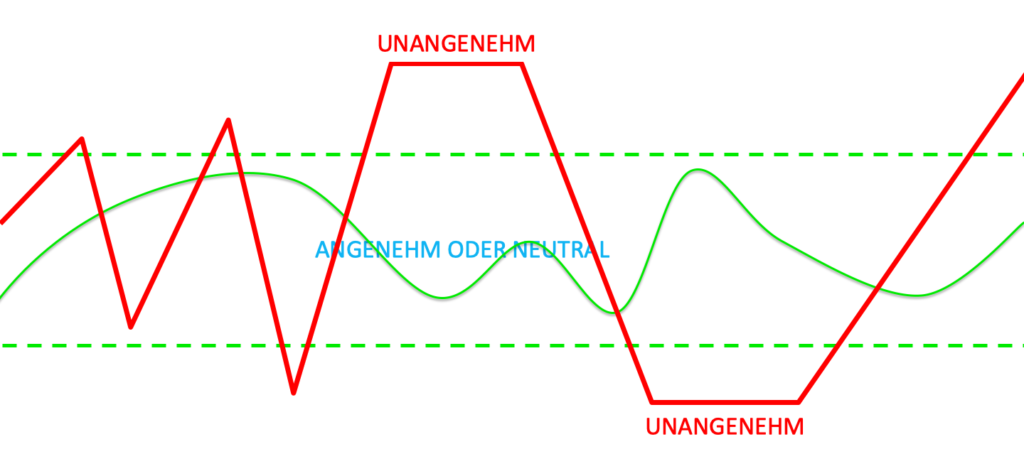

Over time, stress overload can take a toll on our Stress and Recovery Curve. It can lose flexibility, meaning that even small things can send us into hyperarousal or hypoarousal.

The good news is: even after a long period of stress overload, your stress and recovery curve can regain its flexibility. Just like a garden that has been devastated by a storm, your flexibility can grow back with extra care.

Under a normal amount of stress, the nervous system can shift flexibly between activation and recovery. As long as the curve runs smoothly, our physical state is neutral or pleasant. We can be angry, sad, excited or exhausted and still be “in the curve”, meaning that we are still able to control how we respond to the situation at hand.

Facing more stress than we are used to puts a strong demand on our nervous system: the curve takes a sharp upward turn. This is often a helpful reaction, for example in a competition or when we need to protect ourselves or others from danger.

However, if this demand is extreme or continues for a long time, our nervous system gets overloaded. When this happens, our body reacts. This usually feels quite unpleasant.

Under extreme stress, the body jumpstarts us into a state called “hyperarousal”, which means that it is ready to do whatever it takes to ensure safety. Heart, muscles, breathing and the entire nervous system go into overdrive. As helpful as this is when we are in danger, it can take a toll on our wellbeing if it continues for too long. Physically, emotionally and especially in our ability to relate to other people.

Our body is only able to manage hyperarousal for a limited period of time because it costs an extreme amount of energy. What can follow is a natural response: the nervous system can go into “hypoarousal”, which can feel like the body is shutting down or disconnected. Many people describe feeling like they are “numb” or “stuck”. This also costs a lot of energy.

When this happens too often or for too long, the curve can lose flexibility. This can mean that we find ourselves going into overdrive or exhaustion more easily, and more frequently. In both of these extreme states, it costs an extreme amount of energy to care for ourselves and each other.

Paying attention to how your body reacts to stress and wellbeing can help you take care of your Stress and Recovery Curve. You can do this by checking in with your physical state and asking yourself: is it pleasant, neutral or unpleasant? If you notice discomfort, you can choose any activity from the toolkit that helps your body manage stress.